Can you be compensated for an injury while going to or from work in North Carolina?

On its surface, workers’ compensation might seem like a relatively straightforward system. If you’re hurt at work, you are owed compensation from your employer or their insurance company for expenses that arise as a result.

However, things are rarely as cut-and-dried as they first appear—and North Carolina workers’ compensation laws are no different.

For example:

Can you receive workers’ compensation if you hurt on the way to work? What about if you’re headed home after work? What if you were injured during a business trip?

These questions and similar issues unveil a legal grey area that is commonly determined by a concept known as the “going and coming” rule.

What is the “going and coming” rule?

The “going and coming” rule has its roots in the common law and states that an injury occurring while an employee is traveling to and from work is not compensable. An injury must arise out of and in the course of employment in order to be compensable under the North Carolina Workers’ Compensation Act.

The 2 requirements are separate and distinct, and both must be satisfied in order to render an injury compensable:

- Arising out of employment. The term “arising out of” refers to the origin or causal connection of the injury to the employment.

- Arising in the course of employment. The phrase “in the course of” refers to the time, place and circumstances under which the injury by accident occurs.

The rationale and purpose behind the rule

The “going and coming” rule stems from the rationale that the risk of injury while traveling to and from work is common to the public at large. Nevertheless, the courts have recognized that employment begins a reasonable time before actual work begins, continues for a reasonable time after work ends, and includes intervals during the workday for rest and refreshment.

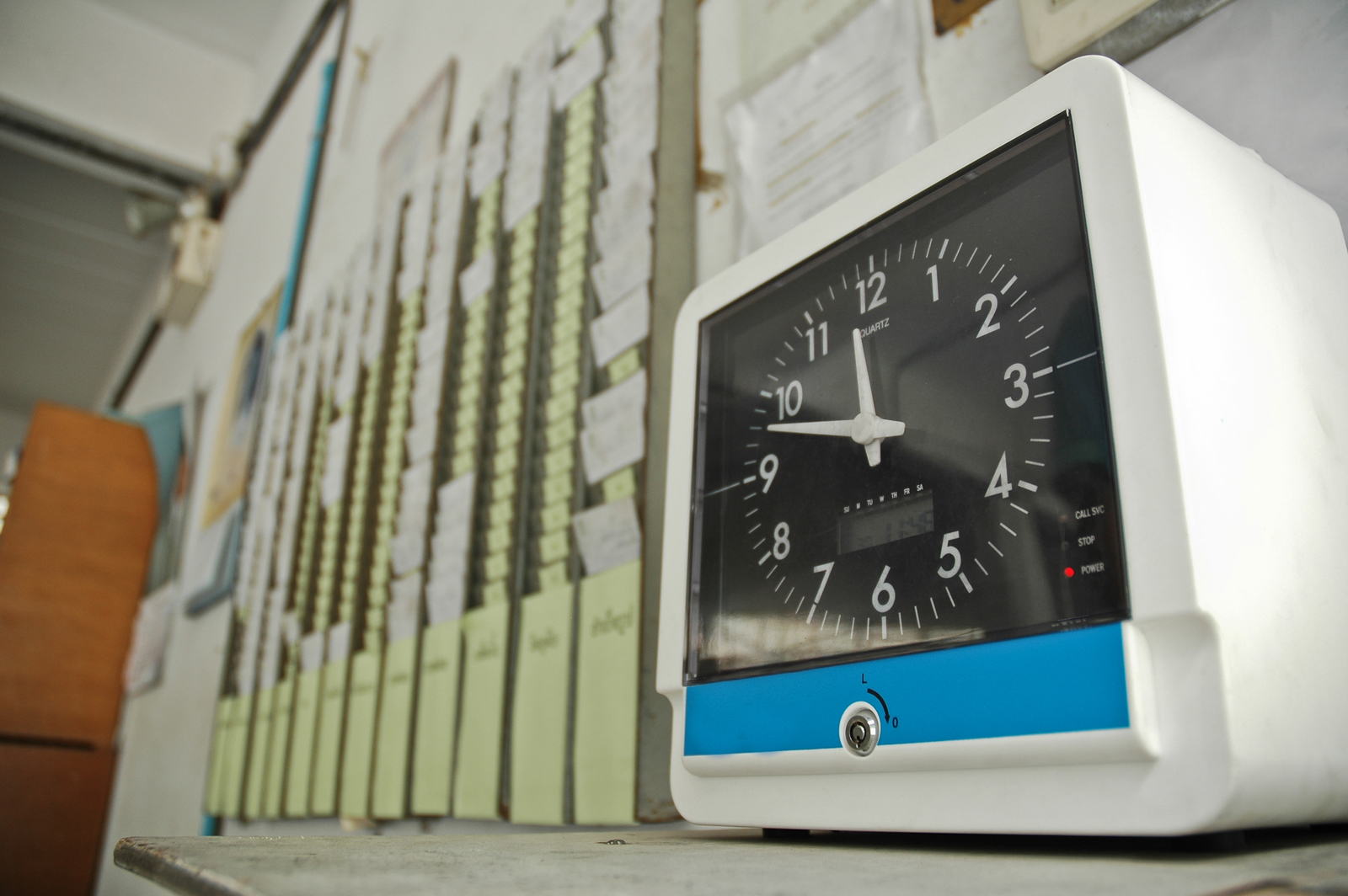

Often, litigation results from injuries that occur during these gray areas of employment—such as during a work break or immediately before/after “clocking” out.

Exceptions to the “going and coming” rule

Generally, the “going and coming” rule provides that an injury occurring while an employee travels to and from work does not satisfy the “in course of employment” prong of the requirements and is therefore not compensable.

There are, however, three categories of situations where the North Carolina courts have refused to apply the going and coming rule as a bar to recovery.

North Carolina courts have deemed an injury to be “in the course of employment” when:

- The injury occurs on the employer’s premises;

- The injury occurs during the employee’s performance of a “special errand” for the employer; or

- The employer either arranges transportation pursuant to an employment contract or the employer compensates the employee for his transportation costs to and from work.

In this article, we will explore the various situations in which the going and coming rule has been applied and how the exceptions to the rule have developed over the years.

Common types of cases involving the “going and coming” rule

The most common applications of the “going and coming” rule involve situations where employees are injured either on the public highways while driving their own vehicle to and from work, or on a parking lot not owned by their employer. The public highway cases focus on the mode of transportation and the reason for traveling, whereas The parking lot cases focus on who is responsible for the ownership, control, and maintenance of the parking lot.

In order for the “going and coming” rule to act as a bar to recovery, none of the 3 exceptions to the rule can apply. In other words, if the injury occurs on a parking lot owned by the employer or on a public highway while the employee is on a special errand for the employer, the injury will be compensable.

Public highway cases (case example)

The clearest example of a workers’ compensation claim being barred by the “going and coming” rule in North Carolina is Wright v. Wake County Public Schools (1991), in which the Court of Appeals held that a part-time school bus driver, who was injured in a car accident immediately after leaving a mandatory school transportation meeting, was not performing a duty arising out of or during the course of his employment. The plaintiff’s duties included driving a school bus and attending school transportation meetings.

On the morning of November 30, 1988, the plaintiff drove his school bus on his designated early morning route. Later that morning, he drove his own car to a school transportation meeting, for which the bus driver was paid a predetermined amount for each meeting. The supervisor encouraged the bus drivers to drive their own cars to the meeting in order to limit the number of school buses in the parking lot.

After the meeting, the plaintiff left the school grounds between 10:00 and 10:30 a.m. in his personal car and was immediately involved in an automobile accident on a public street. He was not required to report back to the school until 2:00-2:15 p.m. and was on his own personal business after leaving the morning meeting.

The Commission held that because the plaintiff was going about his personal business at the time of the accident, he did not sustain an injury by accident arising out of and in the course of his employment.

In his appeal, the plaintiff argued that because his presence was required at the meeting and because he was directed to drive his own car to the meeting, the accident did, in fact, occur in the course of his employment. However, the Court of Appeals rejected this argument and held that since “being required to drive to a meeting is no different from being required to drive one’s car to work,” the plaintiff is barred from recovery under the Workers’ Compensation Act.

Parking lot cases (case example)

The majority of parking lot cases hinge on whether or not the employer owns, maintains, or controls the parking lot on which the employee is injured. In Royster v. Culp, Inc. (1996), the North Carolina Supreme Court adopted a “bright line” test that deemed only those injuries sustained on parking lots owned, controlled, or maintained by the employer to be compensable. Thus, the current trend is to deny workers’ compensation benefits if the employee is injured off-premises while taking a necessary route between the place of employment and the employer’s parking lot.

In the Royster case, the plaintiff was struck by a car and injured while attempting to cross a public highway that separated his place of employment from a parking lot that was owned and operated by his employer. The Deputy Commissioner and the Full Commission denied benefits, but in a unanimous opinion the Court of Appeals reversed the decision.

The Supreme Court then granted discretionary review and reversed the Court of Appeals, ruling with 2 justices dissenting. The Supreme Court stated that the premises exception to the “going and coming” rule did not apply because the injury occurred on a public street. The Court reasoned that the plaintiff was not performing any duties for the employer at the time of the injury and was not exposed to any greater danger than the public generally.

3 exceptions to the “going and coming” rule

1. The premises exception

As a general rule, injuries occurring while an employee is going to or coming from work are not compensable. However, when an employee is injured while going to or coming from work but is on the premises (property) that is owned, controlled, or maintained by the employer, then the injury is compensable.

The general trend by the Supreme Court is to deny compensability if the injury occurs off-premises, even if the place where the injury occurs is a necessary route between one area of employer-owned property to another area of employer-owned property. The theory behind the narrow reading of the premises exception is that crossing public roads and navigating public walkways are risks inherent to the general public and are not special hazards caused by employment.

Case example: Smallwood v. Eason (1997)

This narrow reading of the premises exception was most recently affirmed by the Supreme Court in a case known as Smallwood v. Eason (1997). In Smallwood, plaintiffs Peggy Smallwood and Craig Morning were picked up after their shift at the Perdue Farms maintenance garage by Mr. Morning’s brother, Duane. Duane was driving an automobile owned by Laura Grant.

At about the same time, a forklift driven by the defendant Curtis Eason and owned by Perdue stalled in the road adjacent to the Perdue facilities. Eason was unable to move the forklift completely out of the road and the plaintiff’s car collided with the forklift causing injury.

The road adjacent to the Perdue facilities was the only means of ingress and egress from the Perdue facility. The road was open to the general public, but no homes or businesses other than Perdue were on the road.

The Court of Appeals held that even though Perdue did not own the road, the employees were at the site of the accident because of their employment. Since the Perdue access road was the only way for plaintiffs to arrive and leave work, and since the accident was due in part to the stalled Perdue forklift, the Court of Appeals held that plaintiffs injuries were not barred by the “going and coming” rule.

However, once again, the North Carolina Supreme Court reversed this holding and relied on Judge Greene’s dissent. Judge Greene cited the Royster and held that the premises exception applies only if the place where the injuries occurred was either owned, maintained, or controlled by the employer. This is so even if the accident occurs at a place the employee is required to traverse in order to access his or her actual place of employment.

Since Perdue did not own, maintain, or control the public road on which the accident occurred, the plaintiffs were not considered in the course and scope of their employment with Perdue at the time of the accident and thus they ruled that the Workers’ Compensation Act did not apply.

It’s important to note that this trend by the North Carolina Supreme Court of not extending the premises exception to an off-premises necessary route is the minority view that has only been reluctantly endorsed by the Court of Appeals. Prior to the Royster case, North Carolina courts commonly held that the premises exception included “adjacent premises used by the employee as a means of ingress and egress with the express or implied consent of the employer.”

Most jurisdictions hold that an injury on a public street or at other off-premises places between a plant and a parking lot is in the course of employment because it is a necessary route between two portions of the employer’s premises.

Although the premises exemption is narrowly applied, both the state and federal courts have been quite clear that if the employer either owns, maintains or controls the premises, including a parking lot, where the employee is injured, that injury will be compensable.

So when employees are injured on parking lots either before or after work, the injury falls within the premises exception to the “going and coming” rule.

Case example: Davis v. Devil Dog Mfg. Co. (1959)

The North Carolina Supreme Court held that the claimant’s broken ankle occurred in the course of her employment because she slipped and fell while on her way to work walking from her parked car in the employer’s parking lot down a clay walk to her employer’s plant. The employer provided the parking lot, maintained the lot, and supervised the activity on the lot.

The court held that “going to and from the parking lot in order to reach and leave her immediate working area was a necessary incident to the claimant’s employment.”

2. The special errand exception

The special errand exception states that when travel is contemplated as part of the employee’s work, injuries occurring during travel are compensable.

The rationale behind the “going and coming” rule is that the risk of injury while traveling to and from work is common to the public at large. However, if an employee is injured while performing a special duty or errand for the employer, the injury is compensable.

The special errand exception encompasses business trips and trips made for both personal and employment reasons (referred to as the “dual-purpose” doctrine). The difficulty in applying the special errand exception is determining when the special errand ends and the “going and coming” rule begins.

Business trips

North Carolina adheres to the rule that employees whose work requires travel away from the employer’s premises are within the course of their employment continuously during such travel, except when there is a distinct departure for a personal errand.

Case example: Martin v. Georgia-Pacific Corp. (1969)

In this case, the plaintiff (Mr. Martin) was staying at a hotel in Milwaukee for a week while on a business trip. Mr. Martin was required to attend classes at the hotel during the day, but he was free to spend his evenings as he wished.

On the night of the injury, Mr. Martin, along with 2 others, walked 3 or 4 blocks to the Milwaukee River and observed some yachts. After walking several blocks, they then decided to go to the steakhouse where they had previously planned to eat dinner. While walking from the river to the steakhouse, Mr. Martin was struck by a car and killed.

The North Carolina Court of Appeals held that Mr. Martin’s injury was compensable because “traveling employees, whether or not on call, usually do receive protection when the injury has its origin in a risk created by the necessity of sleeping or eating away from home.” The theory is that since requiring the employee to stay overnight provides a benefit to the employer, any injury that an employee sustains during his overnight stay is compensable provided that the employee is acting reasonably at the time of his injury.

The Court was of the belief that there was a reasonable relationship between Mr. Martin’s employment and eating meals. Even though he had taken a personal trip to the marina, Mr. Martin was on his way to dinner when he was struck by the car. Since Mr. Martin “was at a place where he might reasonably be at such time and doing what he, as an employee, might reasonably be expected to do,” the Court found that he was acting in the course and scope of his employment and therefore covered by workers’ compensation.

Dual purpose trips

Delineating between when a deviation ends and a special errand begins is where things get tricky.

Under the “dual-purpose rule,” in order for a deviation from the employer’s premises to qualify as a special errand, the employer must receive a benefit from the deviation. The dual-purpose rule applies in North Carolina when “concurrently with an employee’s usual trip to or from work, she performs some service for her employer which would otherwise necessitate a separate trip.”

In other words, if an employee is injured while performing a personal errand, but is within the “dual-purpose rule,” the injury is considered to have arisen within the course and scope of employment and is therefore compensable.

Where the employment necessitates travel, it has been held that the hazards of the route become the hazards of employment.

In past cases, the Supreme Court has articulated the test for applying the dual purpose rule. The Court has stated that if an employee would have canceled the travel if the business no longer required him or her to take the trip, then it is travel that arises out of and in the course of employment. If, on the other hand, the journey would have gone forward even if the business purpose had been canceled, then the travel is personal and the risk is one that the ordinary public would face.

Case example: Creel v. Town of Dover (1997)

In this case, the Court of Appeals addressed the dual purpose doctrine and held that a mayor who was injured while riding his bike to remove a stalled truck was within the special errand exception to the “going and coming” rule and was therefore entitled to workers’ compensation benefits.

On the evening of September 3, 1993, the mayor of the Town of Dover received a request from a city alderman to move a city-owned truck that was blocking traffic in Dover. The mayor possessed the keys to the truck and agreed to move it himself. He left his house on a bicycle, but before reaching the city-owned truck, the mayor first stopped at his place of business and consumed an alcoholic beverage.

The mayor then returned to his bicycle but was thrown from the bike when he struck a mound of dirt. The Deputy Commissioner ruled that the mayor’s injury arose out of his employment and that the defendants failed to prove that plaintiff’s intoxication was a proximate cause of his injury. Both the Full Commission and the Court of Appeals affirmed the decision.

Furthermore, the Court of Appeals held that there was a reasonable relationship between the mayor’s trip to move the city-owned truck and his employment as the mayor. The Court rejected the “going and coming” rule and held that the mayor was on a special errand.

The defendants argued that since the mayor had “no fixed time and space limitations on his employment,” he should not be able to take advantage of the special errand exception. However, the Court noted that even if the plaintiff had no fixed time and place of employment, his journey to move the city-owned truck would nonetheless fall within the course of his employment since that particular duty exposed him to risks of travel.

The Court of Appeals also noted that the mayor would not have been entitled to benefits if he had engaged in a distinct departure on a personal errand. But in this case, since the mayor had ended his deviation and resumed his employment activities when the injury occurred, his injury was compensable.

Acts benefiting an employer “to an appreciable extent”

The general premise of this exception is that if travel is contemplated as a part of the work that benefits an employer, injuries occurring during this travel are compensable. This is often referred to as the “traveling salesman” exception. In actuality, it is just a broad application and extension of the special errand exception.

Some cases apply a combination of the special errand exception, dual-purpose doctrine, and traveling salesman exception to find that injuries occurring while an employee engages in acts that benefit the employer to an appreciable extent are compensable.

Case example: Felton v. Hospital Guild of Thomasville, Inc. (1982)

In this landmark case, the Court of Appeals applied the dual purpose rule and awarded benefits.

The plaintiff (Ms. Felton) was injured when she slipped on her driveway. Ms. Felton was an employee of a hospitality shop. Every day, she was required to pick up goods from the bakery on her way to work to sell in the shop.

On this particular day, Ms. Felton telephoned the local bakery to place the order. She left home shortly after, intending to take a less direct route to the hospitality shop so she could stop by the bakery. She was about 30 feet from her front door and had not quite reached her car when she fell and fractured her hip.

The Court of Appeals held that the “going and coming” rule did not apply since Ms. Felton was on a special errand for her employer at the time of her injury. The Court refused to institute a bright-line test for determining when a special errand begins and ends. The Court then applied the dual purpose rule and found that the purpose of Ms. Felton journey was 2-fold:

- She intended to proceed to work, and

- She intended to proceed to the bakery to pick up the order for the day.

The work of the employee, therefore, created the necessity for the travel and the business purpose of the trip was calculated to further the employer’s business. The Court held Ms. Felton’s claim compensable because “the hazards of the trip became the hazards of her employment.”

Traveling directly from home to a worksite

Most of the confusion concerning “going and coming” claims involve the situation where an employee travels directly from his or her home to a worksite that is other than his or her regular office. Common examples include real estate agents who are injured on the way to show a house, home health care professionals who are injured traveling to the patient’s home, and construction workers going directly to the site of a project.

In all of these cases, the injuries will be found to be compensable since the travel is inherent to the job and is a necessary incident of employment. This is true even if the employee deviates from employment and performs a personal errand.

Case example: Kirk v. State (1995)

In this case, the plaintiff was employed as a security guard at Caledonia Correctional Institute in Halifax County. As a condition of his employment, Mr. Kirk was instructed to complete a 4-week training course at Halifax Community College. He received a letter from the state informing him that there were no on-site accommodations and it would be necessary for him to either drive his personal car to the community college or go to the prison where transportation would take him to the training site.

Mr. Kirk elected to drive his own car from his home to the community college. He was not reimbursed for mileage and was not paid for this travel time. He was in an accident on the way to the community college and suffered injuries.

The court applied the special errand exception and found the injuries to be compensable, holding that “Kirk was required, as a condition of his employment, to attend a 4-week training seminar which was not offered at Caledonia… Therefore, Kirk was on a special errand to attend a training course at the direction of and for the benefit of his employer.”

The court made the distinction between Mr. Kirk’s regular place of employment and the site that he was required to attend. The court indicated that had Mr. Kirk been traveling to the prison, his claim would have been barred by the “going and coming” rule. However, since his employer required him to travel away from the employer’s premises, the special errand exception applied.

How our attorneys can help use the special errand exception to secure benefits

The Court’s recent rulings have broadened the special errand exception by allowing benefits for injuries occurring off-premises, as long as there is a “reasonable relationship” with the employee’s employment.

This broad interpretation of the special errand exception has the potential to swallow the “going and coming” rule. On the one hand, the Supreme Court has said that it wants to limit employer liability by drawing a bright line for the premises/off-premises distinction. On the other hand, the Court refuses to apply a bright-line test in determining when a special errand begins. An employee is therefore conceivably entitled to compensation at any time and anywhere as long as the injury has some “reasonable relationship” to employment.

The entire theory behind the “going and coming” rule is that employees should not be compensated for risks faced equally by the general public. Many of the injuries that have been held to be compensable under the special errand exception are injuries that are equally faced by the general public (slipping in a bagel store, having problems getting into your wife’s car, falling in your driveway, having your car roll down an incline, etc.).

In bringing or defending “going and coming” claims, it is absolutely necessary to examine the reason why the employee was at the particular place where he or she was injured. If the employee is put in a position that might pose a risk, however slight, and the employer benefits from the employee taking that risk, there is an argument that the claim is compensable under the special errand exception.

However, this reasoning is not applied to claims occurring on a necessary route between an employer parking lot and the workplace because presumably the employer does not benefit from that activity. As plaintiff’s attorneys, it’s our job to rely on the broad interpretations of the special errand cases and argue that at the time of the injury the claimant was involved in an activity that bore a reasonable relationship to employment and that activity benefited his or her employer.

3. The transportation exception

Lastly, there have been few cases addressing the transportation exception to the “going and coming” rule. For example, in Puett v. Bahnson Co. (1950), the North Carolina Supreme Court stated that “where transportation is furnished in going to and from work, the injury sustained during that time is compensable… whether the actual vehicle is furnished by the employer or whether the employer furnishes money for said transportation and leaves it to the employee to provide his own mode of transportation.”

Let’s look at some examples of when the transportation exception might apply:

Employer pays or reimburses the cost of transportation

Claims are compensable when an employee is injured while traveling to and from work in his own vehicle if the employer has arranged to compensate the employee for either their time or their transportation costs.

Case example: Puett v. Bahnson Co. (1950)

The plaintiffs were employed to install an air conditioning system in a cotton mill 15 or 20 miles from their home. They commuted back and forth from the cotton mill each day, using their personal vehicles and alternating among the personal vehicles of each of the 3 employees. The employer paid each of the 3 plaintiffs an additional sum of money each week to cover living expenses and the expense of traveling to and from the cotton mill, which was the place of employment.

On the day of the accident, at about 6:30 or 7:00 a.m., while on their way to the cotton mill from their homes, the 3 employees were involved in a motor vehicle accident which resulted in injury to all 3 plaintiffs.

The North Carolina Supreme Court held that the workers’ compensation claims of the 3 injured employees were compensable as an exception to the “going and coming” rule since, under the terms of their employment, transportation allowances were made by their employer to cover the cost of such transportation.

In order for the claim to be found compensable on the basis of employer compensation for travel, it must be clear where the employee is going.

Employer furnishes transportation

When an employer provides a transportation conveyance to his or her employees as an incident to the contract of employment, and the accident occurs while going to or from work, then a claim may be compensable as arising out of and in the course of the employment. However, if the provision of the transportation is “gratuitous” or a mere accommodation, then the case falls under the general “going and coming” rule and the claim is not compensable.

Case example: Travelers Ins. Co. v. Curry (1976)

In this case, the employer let 1 employee use a company motor vehicle to transport 2 other employees from Greensboro to Lexington. This motor vehicle was used regularly every day by the 1 employee to transport the 2 other employees to work in Lexington. The 1 employee who drove the company truck was compensated for this as part of his job. The other 2 employees were not paid for the time while they were commuting to work.

At 7:00 a.m. on the date of the accident, while the 1 employee was transporting the other 2 employees to the work site, a motor vehicle accident occurred and the 2 passenger employees were injured.

The Full Commission found that the transportation was not provided to the 2 injured employees pursuant to an express or implied term of a contract of employment, that the 2 employees were not entitled to the transportation furnished by the employer, and the 2 employees were not required by their employer to use such transportation in commuting to and from work.

The Full Commission found that since the transportation furnished by the employer was gratuitous and a mere accommodation, the injured employees were not within the course and scope of their employment when the accident occurred—and therefore they were not eligible for workers’ compensation benefits.

Courtesy rides given by an employer do not, generally, give rise to liability under workers’ compensation statutes. The transportation must be furnished as a real incident of the employment to come within the rule.

In other words:

There must exist an express or implied obligation on the part of the employer to provide transportation.

If an employer merely permits or authorizes the use of his or her facilities by an employee to return home, it is not considered as being in the course of employment, but as a convenience to the employee. An injury happening under such circumstances does not bring the employee within the Workers’ Compensation Act.

An overview of how the “going and coming” rule applies to workers’ compensation

In summary, throughout this article we have explored the general “going and coming” rule when it comes to workers’ compensation, which states that injuries sustained while an employee is traveling to and from work are not compensable because such injuries do not arise out of or in the course of employment.

This rule, however, is subject to 3 exceptions.

- The premises exception grants compensation even though the employee has not yet commenced his or her specific job task if the injury occurred on property owned, maintained or controlled by the employer. This exception is strictly interpreted and does not pertain to injuries occurring on off-premises necessary routes of travel.

- The special errand exception allows recovery when the employer exercises sufficient control over the employee so that the task is of an “appreciable benefit” to the employer. This includes business trips, where an employee is deemed to be in continuous employment unless the employee deviates on a personal errand. Even if an employee deviates from employment, as soon as the employee begins to return to his employer’s business, such as returning to a hotel, or traveling to and from meals, the employee regains the protection of the special errand exception. The special errand exception applies even if the employee is engaged in activities both for his own purpose and for the employer’s purpose. A special errand has no finite beginning or end, and employees are entitled to protection as long as the special errand bears a “reasonable relationship” to the employment.

- The transportation exception says that injuries may be deemed compensable when, under the terms of the employment or as an incident to the contract of employment, allowances are made by the employer to cover the cost of transportation. If an employer furnishes the transportation, it must be pursuant to an employment contract or agreement, and cannot be a mere gratuity or accommodation. On the other hand, as long as the employer is compensating an employee for his or her travel time or transportation expenses, any injury occurring while the employee travels to and from work in their own vehicle is compensable as long as it can be proven where the employee was actually going.

The modern trend with regard to the “going and coming” rule is to narrowly apply the premises exception and transportation exceptions, but to broadly apply the special errand exceptions. The Supreme Court has taken a restrictive view in strictly applying the rule in the context of the premises and transportation exceptions. However, there is some indication that the special errand exception may swallow the rule if that exception continues to be broadly interpreted and applied.

At one extreme is the Supreme Court case Royster where the Court refused to award benefits to an employee who crossed a public road in order to get from the employer-owned parking lot to the employer-owned main facility. At the other extreme is the Supreme Court’s holding in Powers where it granted benefits to an employee who was struck by his own car in his own driveway.

Until these conceptual inconsistencies are resolved, it’s vital that injured workers choose a North Carolina workers’ compensation attorney who is deeply knowledgeable about historic “going and coming” cases and the precedents they set, and highly experienced in arguing these challenging cases.